What is Alzheimer’s?

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, a general term for memory loss and other cognitive abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases.

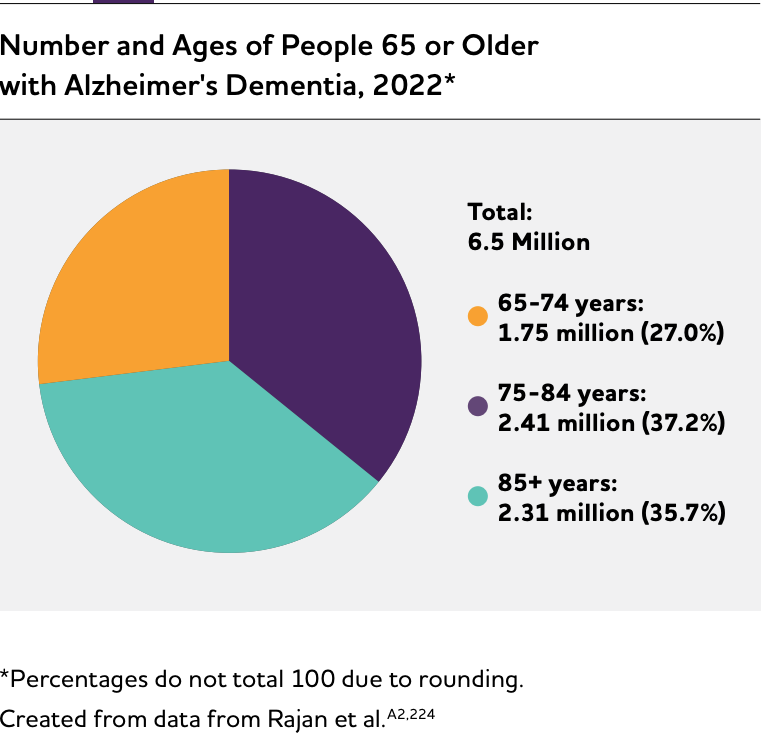

Alzheimer’s is not a normal part of aging. The greatest known risk factor is increasing age, and the majority of people with Alzheimer’s are 65 and older. Alzheimer’s disease is considered to be younger-onset Alzheimer’s if it affects a person under 65. Younger-onset can also be referred to as early-onset Alzheimer’s. People with younger-onset Alzheimer’s can be in the early, middle or late stage of the disease.

Alzheimer’s worsens over time. Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, where dementia symptoms gradually worsen over a number of years. In its early stages, memory loss is mild, but with late-stage Alzheimer’s, individuals lose the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to their environment. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives 4 to 8 years after diagnosis but can live as long as 20 years, depending on other factors.

Alzheimer’s has no cure, but one treatment — aducanumab (Aduhelm™) — is the first therapy to demonstrate that removing amyloid, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, from the brain is reasonably likely to reduce cognitive and functional decline in people living with early Alzheimer’s. Other treatments can temporarily slow the worsening of dementia symptoms and improve quality of life for those with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. Today, there is a worldwide effort underway to find better ways to treat the disease, delay its onset and prevent it from developing.

What causes dementia?

The hallmark pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease are the accumulation of the protein beta-amyloid (plaques) outside neurons and twisted strands of the protein tau (tangles) inside neurons in the brain. These changes are accompanied by the death of neurons and damage to brain tissue. Alzheimer’s is a slowly progressive brain disease that begins many years before symptoms emerge. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for an estimated 60% to 80% of cases.

Recent large autopsy studies show that more than half of individuals with Alzheimer’s dementia have Alzheimer’s disease brain changes (pathology) as well as the brain changes of one or more other causes of dementia, such as cerebrovascular disease or Lewy body disease. This is called mixed pathologies, and if recognized during life is called mixed dementia.

Symptoms

Difficulty remembering recent conversations, names or events is often an early symptom; apathy and depression are also often early symptoms. Later symptoms include impaired communication, disorientation, confusion, poor judgment, behavioral changes and, ultimately, difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking.

Stages of Alzheimer’s

While we know the Alzheimer’s disease continuum starts with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (no symptoms) and ends with severe Alzheimer’s dementia (severe symptoms), how long individuals spend in each part of the continuum varies. The length of each part of the continuum is influenced by age, genetics, biological sex and other factors.

Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease

In this phase, individuals may have measurable brain changes that indicate the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease (biomarkers), but they have not yet developed symptoms such as memory loss. Examples of Alzheimer’s biomarkers include abnormal levels of beta-amyloid as shown on positron emission tomography (PET) scans and in analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), changes in tau protein in CSF and plasma, and decreased metabolism of glucose as shown on PET scans. When the early changes of Alzheimer’s disease occur, the brain compensates for them, enabling individuals to continue to function normally.

Although research settings have the tools and expertise to identify some of the early brain changes of Alzheimer’s, additional research is needed to fine-tune the tools’ accuracy before they become available for widespread use in hospitals, doctors’ offices and other clinical settings. It is important to note that not all individuals with evidence of Alzheimer’s-related brain changes go on to develop symptoms of MCI or dementia due to Alzheimer’s. For example, some individuals have beta-amyloid plaques at death but did not have memory or thinking problems in life.

MCI Due to Alzheimer’s Disease

People with MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease have biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s brain changes plus new but subtle symptoms such as problems with memory, language and thinking. These cognitive problems may be noticeable to the individual, family members and friends, but not to others, and they may not interfere with individuals’ ability to carry out everyday activities. The subtle problems with memory, language and thinking abilities occur when the brain can no longer compensate for the damage and death of neurons caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

Among those with MCI, about 15% develop dementia after two years. About one-third develop dementia due to Alzheimer’s within five years. However, some individuals with MCI revert to normal cognition or do not have additional cognitive decline. In other cases, such as when a medication inadvertently causes cognitive changes, MCI is mistakenly diagnosed and cognitive changes can be reversed. Identifying which individuals with MCI are more likely to develop dementia is a major goal of current research.

Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease

Dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, or Alzheimer’s dementia, is characterized by noticeable memory, language, thinking or behavioral symptoms that impair a person’s ability to function in daily life, combined with biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s-related brain changes. As Alzheimer’s progresses, individuals commonly experience multiple types of symptoms that change with time. These symptoms reflect the degree of damage to neurons in different parts of the brain. The pace at which symptoms of dementia advance from mild to moderate to severe differs from person to person.

Mild Alzheimer’s Dementia

In the mild stage of Alzheimer’s dementia, most people are able to function independently in many areas but are likely to require assistance with some activities to maximize independence and remain safe. Handling money and paying bills may be especially challenging, and they may need more time to complete common daily tasks. They may still be able to drive, work and participate in their favorite activities.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Dementia

In the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s dementia, which is often the longest stage, individuals experience more problems with memory and language, are more likely to become confused, and find it harder to complete multistep tasks such as bathing and dressing. They may become incontinent at times, and they may start having personality and behavioral changes, including suspiciousness and agitation. They may also begin to have problems recognizing loved ones.

Severe Alzheimer’s Dementia

In the severe stage of Alzheimer’s dementia, individuals’ ability to communicate verbally is greatly diminished, and they are likely to require around-the-clock care. Because of damage to areas of the brain involved in movement, individuals become bed-bound. Being bed-bound makes them vulnerable to physical complications including blood clots, skin infections and sepsis, which triggers body-wide inflammation that can result in organ failure. Damage to areas of the brain that control swallowing makes it difficult to eat and drink. This can result in individuals swallowing food into the trachea (windpipe) instead of the esophagus (food pipe). Because of this, food particles may be deposited in the lungs and cause lung infection. This type of infection is called aspiration pneumonia, and it is a contributing cause of death among many individuals with Alzheimer’s

Signs of Alzheimer’s

Memory loss that disrupts daily life:

One of the most common signs of Alzheimer’s dementia, especially in the early stage, is forgetting recently learned information. Others include asking the same questions over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (for example, reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things that used to be handled on one’s own.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later.

Challenges in planning or solving problems:

Some people experience changes in their ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. They may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills.

Difficulty completing familiar tasks:

People with Alzheimer’s often find it hard to complete daily tasks. Sometimes, people have trouble driving to a familiar location, organizing a grocery list or remembering the rules of a favorite game.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Occasionally needing help to use microwave settings or record a television show.

Confusion with time or place:

People living with Alzheimer’s can lose track of dates, seasons and the passage of time. They may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they forget where they are or how they got there.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Getting confused about the day of the week but figuring it out later.

Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships:

For some people, having vision problems is a sign of Alzheimer’s. They may also have problems judging distance and determining color and contrast, causing issues with driving.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Vision changes related to cataracts.

New problems with words in speaking or writing:

People living with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble naming a familiar object or use the wrong name (e.g., calling a watch a “hand clock”)

Typical Age-Related Changes: Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps:

People living with Alzheimer’s may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them. They may accuse others of stealing, especially as the disease progresses.

Typical Age-Related Changes:Misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them.

Decreased or poor judgment:

Individuals may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money or pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Making a bad decision or mistake once in a while, such as neglecting to schedule an oil change for a car.

Withdrawal from work or social activities:

People living with Alzheimer’s disease may experience changes in the ability to hold or follow a conversation. As a result, they may withdraw from hobbies, social activities or other engagements. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite sports team or activity.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Sometimes feeling uninterested in family and social obligations.

Changes in mood, personality, and behavior:

The mood and personalities of people living with Alzheimer’s can change. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, at work, with friends or when out of their comfort zones.

Typical Age-Related Changes: Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.

Alzheimer’s Treatments

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved six drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Five of these drugs — donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine and memantine combined with donepezil — temporarily treat Alzheimer’s symptoms but do not change the underlying brain changes of Alzheimer’s or alter the course of the disease. With the exception of memantine, they improve symptoms by increasing the amount of chemicals called neurotransmitters in the brain. Memantine protects the brain from a neurotransmitter called glutamate that overstimulates neurons and can damage them. These five drugs may have relatively mild side effects, such as headache and nausea. Learn more.

Active Management of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease

Studies have consistently shown that proactive management of Alzheimer’s and other dementias can improve the quality of life of affected individuals and their caregivers. Proactive management includes:

- Appropriate use of available treatment options.

- Effective management of coexisting conditions.

- Providing family caregivers with effective training in managing the day-to-day life of the care recipient.

- Coordination of care among physicians, other health care professionals and lay caregivers.

- Participation in activities that are meaningful to the individual with dementia and bring purpose to their life.

- Maintaining a sense of self-identity and relationships with others.

- Having opportunities to connect with others living with dementia; support groups and supportive services are examples of such opportunities.

- Becoming educated about the disease.

- Planning for the future. To learn more about Alzheimer’s disease, as well as practical information for living with Alzheimer’s and being a caregiver, visit alz.org

Mortality & Morbidity

1 in 3 seniors dies with Alzheimier’s or another dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease was officially listed as the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States in 2019 and the seventh-leading cause of death in 2020 and 2021, when COVID-19 entered the ranks of the top 10 causes of death.

Alzheimer’s disease remains the fifth-leading cause of death among individuals age 65 and older. However, it may cause even more deaths than official sources recognize. Alzheimer’s is also a leading cause of disability and poor health (morbidity) in older adults. Before a person with Alzheimer’s dies, they live through years of morbidity as the disease progresses.

Deaths from Alzheimer’s Disease

The data presented in this section are through 2019. These data precede the COVID-19 pandemic and give an accurate representation of long-term trends in mortality and morbidity due to Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the United States prior to the large increase in deaths due to COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. See the box “The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Deaths from Alzheimer’s Disease” for a discussion of the dramatic effect of the pandemic on Alzheimer’s mortality. In this section, “deaths from Alzheimer’s disease” refers to what is officially reported on death certificates. It is difficult to determine how many deaths are caused by Alzheimer’s disease each year because of the way causes of death are recorded. According to data from the CDC, 121,499 people died from Alzheimer’s disease in 2019, the latest year for which data are available.

The CDC considers a person to have died from Alzheimer’s if the death certificate lists Alzheimer’s as the underlying cause of death, defined as “the disease or injury which initiated the train of events leading directly to death.”362 Note that while death certificates use the term “Alzheimer’s disease”, the determination is made based on clinical symptoms in almost every case, and thus more closely aligns with “Alzheimer’s dementia” as we have defined it in previous sections of this report; to remain consistent with the CDC terminology for causes of death, we use the terms “Alzheimer’s disease” for this section.

The number of deaths from dementia of any type is much higher than the number of reported Alzheimer’s deaths. In 2019, some form of dementia was the officially recorded underlying cause of death for 271,872 individuals (this includes the 121,499 from Alzheimer’s disease). Therefore, the number of deaths from all causes of dementia, even as listed on death certificates, is more than twice as high as the number of reported Alzheimer’s deaths alone. Severe dementia frequently causes complications such as immobility, swallowing disorders and malnutrition that significantly increase the risk of serious acute conditions that can cause death. One such condition is pneumonia (infection of the lungs), which is the most commonly identified immediate cause of death among older adults with Alzheimer’s or other dementias. One preCOVID-19 autopsy study found that respiratory system diseases were the immediate cause of death in more than half of people with Alzheimer’s dementia, followed by circulatory system disease in about a quarter.

Death certificates for individuals with Alzheimer’s often list acute conditions such as pneumonia as the primary cause of death rather than Alzheimer’s. As a result, people with Alzheimer’s dementia who die due to these acute conditions may not be counted among the number of people who die from Alzheimer’s disease, even though Alzheimer’s disease may well have caused the acute condition listed on the death certificate. This difficulty in using death certificates to determine the number of deaths from Alzheimer’s and other dementias has been referred to as a “blurred distinction between death with dementia and death from dementia.”

Another way to determine the number of deaths from Alzheimer’s dementia is through calculations that compare the estimated risk of death in those who have Alzheimer’s dementia with the estimated risk of death in those who do not have Alzheimer’s dementia. Learn more in the full study.

Duration of Illness from Diagnosis to Death

Studies indicate that people age 65 and older survive an average of four to eight years after a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia, yet some live as long as 20 years with Alzheimer’s dementia. his reflects the slow, insidious and uncertain progression of Alzheimer’s. A person who lives from age 70 to age 80 with Alzheimer’s dementia will spend an average of 40% of this time in the severe stage. Much of this time will be spent in a nursing home. At age 80, approximately 75% of people with Alzheimer’s dementia live in a nursing home compared with only 4% of the general population age 80. In all, an estimated two-thirds of those who die of dementia do so in nursing homes, compared with 20% of people with cancer and 28% of people dying from all other conditions.

The Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease

The long duration of illness before death contributes significantly to the public health impact of Alzheimer’s disease because much of that time is spent in a state of severe disability and dependence. Scientists have developed methods to attempt to measure and compare the burden of different diseases on a population in a way that takes into account not only the number of people with the condition, but also the number of years of life lost due to that disease and the number of healthy years of life lost by virtue of being in a state of disability. One measure of disease burden is called disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is the sum of the number of years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature mortality and the number of years lived with disability (YLDs), totaled across all those with the disease or injury.

These measures indicate that Alzheimer’s is a very burdensome disease, not only to the individuals with the disease, but also to their families and informal caregivers, and that the burden of Alzheimer’s has increased more dramatically in the United States than the burden of other diseases in recent years. According to the most recent Global Burden of Disease classification system, Alzheimer’s disease rose from the 12th most burdensome disease or injury in the United States in 1990 to the sixth in 2016 in terms of DALYs. In 2016, Alzheimer’s disease was the fourth highest disease or injury in terms of YLLs and the 19th in terms of YLDs.

These estimates should be interpreted with consideration of challenges in the availability of data across time and place and the incorporation of disability. These Alzheimer’s burden estimates use different sources for each state in a given year, and a specific source of data may differ in data included across years. Models used to generate these estimates of Alzheimer’s burden assume a year lived with disability counts as less than a year lived without disability. Models do not account for the context in which disability is experienced, including social support and economic resources, which may vary widely. These variations in data sources and consideration of disability may limit the value of these metrics and the comparability of Alzheimer’s estimates across states and across years.

Alzheimer’s Caregivers

Family members and friends provided more than $271 billion in unpaid care to people living with Alzheimer’s and other dementias in 2021. Caregiving refers to attending to another person’s health needs and well-being.

Who Are the Caregivers?

- Several sources have examined the demographic background of family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s or other dementias in the United States.

- Approximately two-thirds of dementia caregivers are women.

- About 30% of caregivers are age 65 or older.

- Over 60% of caregivers are married, living with a partner or in a long-term relationship.

- Over half of caregivers are providing assistance to a parent or in-law with dementia.

- Approximately 10% of caregivers provide help to a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia.

- Two-thirds of caregivers are White, 10% are Black, 8% are Hispanic, and 5% are Asian American. The remaining 10% represent a variety of other racial/ ethnic groups.

- Approximately 40% of dementia caregivers have a college degree or more of education.

- Forty-one percent of caregivers have a household income of $50,000 or less.

- Among primary caregivers (individuals who indicate having the most responsibility for helping their relatives) of people with dementia, over half take care of their parents.

- Most caregivers (66%) live with the person with dementia in the community.

- Approximately one-quarter of dementia caregivers are “sandwich generation” caregivers — meaning that they care not only for an aging parent but also for at least one child.

- Twenty-three percent of caregivers ages 18 to 49 help someone with dementia, which is an increase of 7% since 2015.

- Learn more about Alzheimer’s caregiver demographics.

Burden and Stress

- Compared with caregivers of people without dementia, twice as many caregivers of those with dementia indicate substantial emotional, financial and physical difficulties.

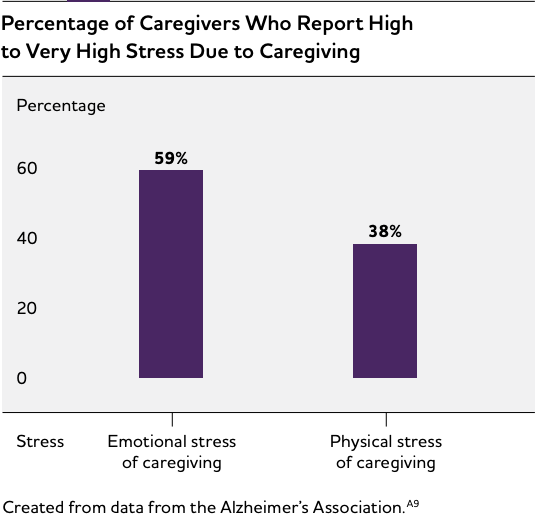

- Fifty-nine percent of family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s or other dementias rated the emotional stress of caregiving as high or very high (Figure 10).

- Spousal dementia caregivers are more likely than non-spousal dementia caregivers to experience increased burden over time. This increased burden also occurs when the person with dementia develops behavioral changes and decreased functional ability.

- Many people with dementia have co-occurring chronic conditions, such as hypertension or arthritis. A national study of caregivers of people with dementia living with additional chronic conditions found that caregivers of people with dementia who had a diagnosis of diabetes or osteoporosis were 2.6 and 2.3 times more likely, respectively, to report emotional difficulties with care compared with caregivers of people with dementia who did not have these co-occurring conditions.

- Learn more

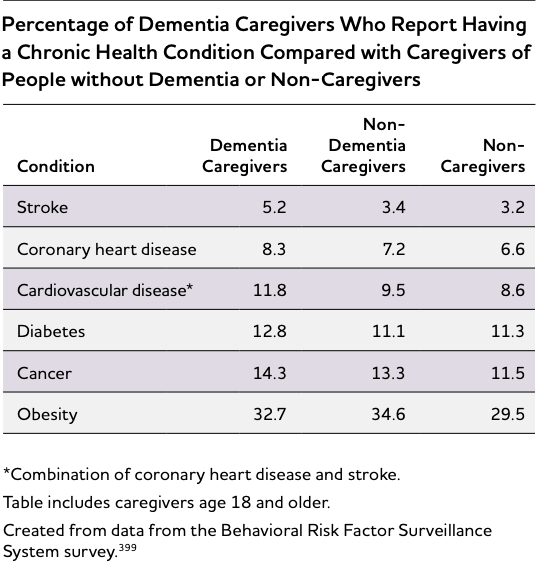

Caregiver’s physical health conditions

For some caregivers, the demands of caregiving may cause declines in their own health. Evidence suggests that the stress of providing dementia care increases caregivers’ susceptibility to disease and health complications. As shown in Figure 10 (see page 43), 38% of Alzheimer’s and other dementia caregivers indicate that the physical stress of caregiving is high to very high. Dementia caregivers are 1.5 times more likely to indicate substantial physical difficulty providing assistance to their care recipients compared with non-dementia caregivers.

The distress associated with caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s or another dementia has also been shown to negatively influence the quality of family caregivers’ sleep. Compared with those of the same age who were not caregivers, caregivers of people with dementia are estimated to lose between 2.4 hours and 3.5 hours of sleep a week. In addition, many caregivers may contend with health challenges of their own. Tables 9 and 10 present data from 44 states and the District of Columbia on caregiver physical and mental health.

Types of caregiver intervention

Case management: Provides assessment, information, planning, referral, care coordination and/or advocacy for family caregivers.

Psychoeducational approaches: Include structured programs that provide information about the disease, resources and services, and about how to expand skills to effectively respond to symptoms of the disease (for example, cognitive impairment, behavioral symptoms and care-related needs). Include lectures, discussions and written materials and are led by professionals with specialized training.

Counseling: Aims to resolve preexisting personal problems that complicate caregiving to reduce conflicts between caregivers and care recipients and/or improve family functioning.

Psychotherapeutic approaches: Involve the establishment of a therapeutic relationship between the caregiver and a professional therapist (for example, cognitive behavioral therapy for caregivers to focus on identifying and modifying beliefs related to emotional distress, developing new behaviors to deal with caregiving demands, and fostering activities that can promote caregiver well-being).

Respite: Provides planned, temporary relief for the caregiver through the provision of substitute care; examples include adult day services and in-home or institutional respite care for a certain number of weekly hours.

Support groups: Are less structured than psychoeducational or psychotherapeutic interventions. Support groups provide caregivers the opportunity to share personal feelings and concerns to overcome feelings of isolation.

Multicomponent approaches: Are characterized by intensive support strategies that combine multiple forms of intervention, such as education, support and respite, into a single, long-term service (often provided for 12 months or more).

Home health care: Home health care allows family caregivers to scale services according to the patient’s needs. Home health care can also educate families and offer resources that allow the person living with Alzheimer’s to remain in the comfort of home. Learn more.

Choosing long-term care is a burden that often falls to adult children and family caregivers. Our team is here to support you throughout the journey. Download our booklet to explore options that are right for your aging loved one and family. Download the booklet here.